Playing the biggest, splashiest, and most ridiculous spells in Magic is one of Commander’s best selling points. EDH isn’t called “Battlecruiser Magic” for nothing. But these format-defining spells won’t ever create incredible moments of gameplay if you don’t have the mana necessary to cast them. Having your favorite cards stuck in hand is no fun. It’s also why mana is the first element in our Unified Theory of Commander. Big spells require big mana, so access to mana sources should be the starting point of every Commander deck.

Think I’m overstating the importance of mana in Commander? Consider the bans issued by the format’s rules committee on cards such as [card]Primeval Titan[/card], [card]Sundering Titan[/card], and [card]Sylvan Primordial[/card]. These cards were not necessarily banned on sheer power level, but on their ability to warp a game around themselves, and potentially creating huge disparities in resources that quickly spiral games out of control.

From the rules committee itself:

One of the concerns that we’ve had recently is the overrepresentation of heavy ramp strategies to the point where it makes up a large proportion of the aggregate decks out there. While we think ramp should be good—this is battlecruiser Magic after all—it’s probably a little too prevalent and needs reining in a bit. With that in mind we’re banning the most egregious offender Primeval Titan.

source

And

One of the criticisms of the format is that if you’re not playing green, you’re behind…

source

I’ll save debating Sheldon Menery about the best color in the format for another article, but for now it’s sufficient to recognize that getting access to lots of mana isn’t just powerful: it’s format-warping. For better or worse, mana is top of mind for the custodians of the format—and that should be enough of an indicator that you too need to give it prime consideration while you are building your deck.

So mana is important. You get it now. But what are you going to do with this information while building a deck? Let’s start with some general rules and then use the My Deck Tickled A Sliver system to help us pick the right options for any commander or color combination.

Start with 40

The first and easiest rule to communicate regarding mana is to start with 40 lands. This doesn’t mean you should start with a giant pile of cards you want to run and then try to make cuts to hit roughly 40 lands in your deck. It means the starting point of every deck should be a commander and forty land slots. That is your empty canvas from which to paint a deck. Only then can you start layering on color to make a complete image.

Now this doesn’t mean your deck needs to end up with exactly forty mana sources. If your commander costs more than five mana and doesn’t have green in its color identity, you may want to consider adding some artifact-based ramp to make sure you can cast your commander more than once per game. My [card]Aurelia[/card] deck packs [card]Sol Ring[/card], [card]Coalition Relic[/card], and [card]Boros Signet[/card] for exactly this reason. Alternatively, you may end up piloting an aggro deck with [card]Krenko, Mob Boss[/card], at the helm and only end up running 32 Mountains and a [card]Strip Mine[/card]. Goblins are cheap and Krenko just needs four lands to get started. So work from a 40-land starting point and adjust up or down into the right number for your commander.

Also make sure to take the mana costs of your spells into consideration, just like any other Magic format. You will need to run more dual lands in a three-color deck than in a deck with just two colors. Try using one of the various ratio-based mana calculators available online to make sure that not only will you get the right number of lands, but the right color sources as well.

Dirt is Better Than Rocks

Another basic rule to keep in mind: “Dirt is better than rocks.” Land-based ramp is generally better than artifact-based ramp. Why? Well, almost every deck is going to be packing artifact removal and sometimes your mana rocks will end up unintentional targets of a [card]Bane of Progress[/card] or an [card]Austere Command[/card], setting you back tremendously. Fewer decks run land destruction and usually those spells are reserved for pesky utility lands like [card]Maze of Ith[/card] or [card]Cabal Coffers[/card]. It will be pretty rare for someone to waste a [card]Strip Mine[/card] on your extra Forest. So it’s generally safer to cast a [card]Kodama’s Reach[/card] than a [card]Simic Signet[/card], even if both are good cards.

Green mages have it easy

This doesn’t mean mana rocks don’t have a place in the format. They still make for excellent additions to most decks and a few really only function because of the power colorless mana ramp provides. You might even be running a land destruction deck (if you don’t like having friends) that strategically uses artifacts to keep casting cards after you resolve an [card]Armageddon[/card]. But in general, be careful of cutting lands and leaning too heavily on artifacts. An overloaded [card]Vandalblast[/card] could choke your access to resources and put your opponents way ahead.

But I’m Not Playing Green

So what if your commander isn’t green and those safe ramp spells aren’t available? There are still plenty of options to help almost any deck “get there” and have an impact on the game. White can run cards such as [card]Land Tax[/card], [card]Tithe[/card], or [card]Kor Cartographer[/card]. Black has the classic [card]Cabal Coffers[/card] and [card]Urborg, Tomb of Yawgmoth[/card] combo, but can also run several creature-based mana doublers like [card]Crypt Ghast[/card] and [card]Nirkana Revenant[/card]. Red and blue are left a little out in the cold here, but in a pinch can use a copying effect such as a [card]Fork[/card] to piggy-back on a green player’s ramp spell.

Despite my previous warning not to rely too heavily on artifact ramp, there are definitely lots of ways to use colorless cards to keep up with the table in mana production. For instance, [card]Staff of Nin[/card] is a phenomenal utility card that draws an extra card each turn to help you dig for lands. Mono-colored decks can also consider [card]Gauntlet of Power[/card] and similar mana doublers to suddenly ramp into big spells. Whatever your colors, I believe there are enough options out there to reach reliable amounts of mana in every deck.

How Much Mana is Enough?

So how much mana is really enough and how fast is it needed? The answers to those questions are difficult to pin down in a format so diverse. The right answer depends on your goal for the deck, the environment in which it’s being played, and the spells it intends to resolve. For a deck to thrive in a very competitive setting, it will need to start resolving or answering threats as early as turn three or four. In a more casual playgroup, those forty basic lands and no acceleration might just do you fine. If everyone else just wants to durdle, why rush?

So you need the right amount of mana at the correct time in each stage of the game to keep playing and answering threats. We will call this our Time to Critical Mana problem. To solve it, consider what your deck wants to be doing on any given turn of the game. This is analogous to curving out in vanilla Magic, but without such strict requirements for success. We can solve Commander’s version of this problem by using some basic statistics. To illustrate, let’s start with a simple critical mana point: the cost of your commander.

Let’s say we are playing an aggro deck and our four-mana commander wants to come online on turn four in as many games as possible. That means from our deck of 99 cards, we need to see at least four sources of mana by the fourth turn. Calculating the chance of this happening is called finding the hypergeometric probability, which is actually a lot less scary than it sounds. We can use an online calculator like this one to do the math for us. To simplify:

Population Size (cards in the deck): 99

Number of Successes in Population (number of mana sources playable by turn four): 40

Sample Size (number of cards you will see by turn four): 11

Number of Successes in Sample (number of mana sources you need to draw): 4

Our probability of success is 72 percent, or roughly three out of every four games. That’s pretty good, but personally, I’d like to be more consistent than that in an aggro deck. If we increase the number of mana sources in our deck to 43, the chance of hitting our critical mana point increases to almost 80 percent, or four out of every five games. That feels a lot better.

Ten minutes crunching numbers will save you hours of bad EDH games

If we apply this math to the win conditions in our deck, it gives us a second critical mana threshold to hit. Let’s assume that our aggro deck is in red and its most potent win condition is [card]Insurrection[/card], an eight-mana spell. We know that the playgroup our fictional deck is competing in has the power to hold off our early aggro attempts, so to keep up with the rest of the decks in a longer game, we want to see enough mana to threaten an [card]Insurrection[/card] by turn 20. What are the chances our 43-mana deck can get there?

Population Size: 99

Number of Successes in Population: 43

Sample Size: 27

Number of Successes in Sample: 8

Probability of Success: 97%

Looks like 43 mana is working out just right for this deck, isn’t it? It fits right into the local metagame and solves the Time to Critical Mana problem quite well. Taking a few moments to consider your mana requirements during the deckbuilding phase will save you a lot of boring games where your favorite cards are stuck in hand.

One additional note about the above math: it doesn’t take mulligans into account. The friendly mulligan rules in most Commander playgroups will allow us to see up to seven additional cards for free. I try not to factor that in too heavily when building my decks, but it does help even out the mana requirements a little. If I add an extra seven cards to the sample size for casting that four-mana commander on turn four, we hit it in 99% of games. That’s pretty good for an aggro deck, isn’t it?

Applying “My Deck Tickled A Sliver”

I don’t mean for the Unified Theory of Commander to result in a bunch of flavorless good-stuff decks that bore players and their opponents alike. Editing a deck for Commander is a process, and so is applying the MDTAS system to make your deck both functional and awesome. So when picking mana sources for your deck, make sure to use the rest of the list to help make cuts.

Haters gonna hate…

Draw is our second most important element, so mana sources that pull cards from your deck are all the more powerful. That’s why green ramp spells are so potent and why I’m willing to accept the ridicule I get for running [card]Knight of the White Orchid[/card] in my Boros decks. Threats and answers that also ramp are so powerful that [card]Primeval Titan[/card] and [card]Sylvan Primordial[/card] got banned, so make sure to pick those responsibly. Finally, synergy is really what makes the format fun for most players, so look for the right mana sources that don’t just get you to your critical mana thresholds, but that also support the rest of the deck. For instance, your bant blink deck is probably better served by a [card]Farhaven Elf[/card] than a [card]Deep Reconnaissance[/card].

Mana in Action: Omnath

To illustrate the power of mana in EDH, let talk a look at an [card]Omnath, Locus of Mana[/card] deck run by my good friend Omid.

[deck title=Omnom’s Mana]

[Creatures]

*1 Gyre Sage

*1 Primordial Hydra

*1 Scavenging Ooze

*1 Borderland Ranger

*1 Courser of Kruphix

*1 Dungrove Elder

*1 Eternal Witness

*1 Fierce Empath

*1 Omnath, Locus of Mana

*1 Brawn

*1 Karametra’s Acolyte

*1 Nylea, God of the Hunt

*1 Oracle of Mul Daya

*1 Solemn Simulacrum

*1 Wolfbriar Elemental

*1 Yeva, Nature’s Herald

*1 Acidic Slime

*1 Garruk’s Packleader

*1 Heroes’ Bane

*1 Seedborn Muse

*1 Brutalizer Exarch

*1 Deadwood Treefolk

*1 Hydra Broodmaster

*1 Primalcrux

*1 Rampaging Baloths

*1 Sakiko, Mother of Summer

*1 Soul of the Harvest

*1 Vigor

*1 Avenger of Zendikar

*1 Moldgraf Monstrosity

*1 Archetype of Endurance

*1 Colossus of Akros

*1 Craterhoof Behemoth

*1 Terastodon

*1 Vorinclex, Voice of Hunger

*1 Woodfall Primus

*1 Artisan of Kozilek

*1 Pathrazer of Ulamog

*1 It That Betrays

[/Creatures]

[Spells]

*1 Green Sun’s Zenith

*1 Sol Ring

*1 Doubling Cube

*1 Unravel the Aether

*1 Bow of Nylea

*1 Genesis Wave

*1 Krosan Grip

*1 Sword of Feast and Famine

*1 Sword of Light and Shadow

*1 Whispersilk Cloak

*1 Bear Umbra

*1 General’s Kabuto

*1 Into the Wilds

*1 Momentous Fall

*1 Triumph of the Hordes

*1 Asceticism

*1 Dictate of Karametra

*1 Garruk, Primal Hunter

*1 Gilded Lotus

*1 Overrun

*1 Caged Sun

*1 Garruk, Caller of Beasts

*1 Primeval Bounty

*1 Akroma’s Memorial

*1 Boundless Realms

*1 Eldrazi Conscription

*1 Primal Surge

[/Spells]

[Lands]

*33 Forest

*1 Oran Rief, the Vastwood

[/Lands]

[/deck]

While I tend to be a Spike in practice, I’m a Timmy at heart. So I’m genuinely excited whenever Omid breaks out this deck. Utilizing Omnath’s ability to save mana across turns, he can start threatening the board with both serious commander damage and begin dropping huge green monsters to terrorize the table as early as turn four. I’ve seen this deck resolve a [card]Primal Surge[/card] before turn six on more than one occasion. The suspense of each card reveal, the groaning when it hits an eldrazi or the laughter when the second card is a sorcery—all of that adds a lot of fun to the table.

Approves of this deck!

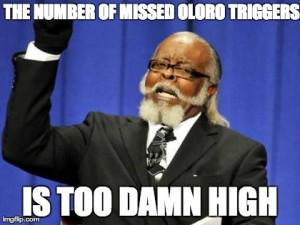

Unfortunately, the deck isn’t always so consistent. When Omnath hits the board early and sticks, the deck generally has plenty of mana available to cast big cards. If his general gets removed or tucked before my friend is able to get other mana sources into play, the deck can quickly get jammed up and those glorious green monsters get stuck in hand. When this happens, it would be easy to blame one’s opponents and complain that they aren’t letting Omnath have any fun, but if we look at the deck’s Time to Critical Mana, then we can see why the deck tends to whimper as often as it roars.

Scroll up and look at the lands again. This deck is only running 34. This initially seems reasonable because Omnath only costs three, acts as a mana battery, and there are a number of mana doublers in the deck. The deck is also running a few creature-based mana accelerators such as [card]Gyre Sage[/card] and [card]Karametra’s Acolyte[/card]. But are these sources really enough? It’s a bit hard to pick a critical mana point with so many huge creatures, but I believe six mana is probably a reasonable starting point. Of the 34 creatures in the deck, 11 cost six mana or more, and that’s also the power threshold at which those creatures start to become particularly threatening to the table.

Counting the lands, creatures, and artifacts that can produce mana and be cast before turn six, the deck has 41 mana sources. That means if Omnath’s pilot doesn’t mulligan aggressively for lands, the deck only has a 46-percent chance of hitting six mana by turn six. By turn eight, the chances have only improved to 65-percent, while the rest of the players at the table are aggressively developing their board states. Meanwhile, 26 cards—more than a quarter of the deck—cost six mana or more and may be piling up in hand. So confronted by a [card]Swords to Plowshares[/card] or an early [card]Wrath of God[/card], this otherwise brilliant deck, that is both fun to play with and against, suddenly has a 50-50 shot of going nowhere.

Now, Omid is a great Magic player and I’ve learned quite a bit about Commander playing with him over the last year. When we went over the math together, he instantly realized that he should probably put a few more Forests into the deck. He just hadn’t previously paused to do the math this way. This tells me that even smart, experienced players can overlook the importance of mana in their EDH decks, especially when focusing on synergy first can make the deck feel explosive and fun in specific instances. Cutting a few cards for Forests, however painful that might seem, isn’t likely to reduce the joy of piloting this Timmy-inspired Omnath build. It will actually help the deck become more consistent and hopefully increase the fun for everyone at our table.

Conclusion

If you want to play Battlecruiser Magic, make sure to start with your mana base. Do a little math after each round of edits to make sure you can reliably hit your critical mana on the right turns. Whether your deck intends to be a proper warship or just a rubber ducky, your favorite cards will get stuck in dry dock without the resources necessary to launch them [Ed. note—Funny, when I think of battlecruisers, I’m not thinking of water. I’m thinking of this.] Keep mana at the top of your mind during the deck building process and the final product will consistently get the chance to create that fun and interaction we all crave from the Commander format.

Have comments on building a strong mana base for your Commander deck? You know what to do!